Linux at 25: Kernel Development by the Numbers

- By David Ramel

- August 23, 2016

With this week marking the 25th anniversary of the open source Linux OS, The Linux Foundation has issued a new report on the massive development effort that shapes the Linux kernel.

That foundational OS component has been built by some 14,000 contributing developers from more than 1,300 companies since these metrics started being tracked in 2005, according to the just-published Linux Kernel Development report (free download upon providing registration info).

Part of a regular report series, the new study was designed to answer questions about the development effort, such as: how fast it's going, who is doing it, what they are doing and who is sponsoring it.

"The kernel which forms the core of the Linux system is the result of one of the largest cooperative software projects ever attempted," says the report, authored by Jonathan Corbet and Greg Kroah-Hartman. The authors claim the Linux kernel project involves more developers than any other open source project. Coincidentally, benefitting from the Git source code management system, it's also one of the most well-documented projects.

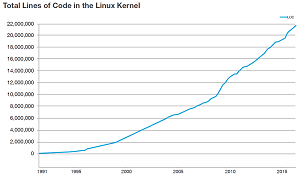

The Linux OS itself is also a moving target, constantly under development. "Every day, 10,800 lines of code are added, 5,300 lines of code are removed, and 1,875 lines of code are modified," said a blog post published yesterday by The Linux Foundation.

[Click on image for larger view.]

Nearing 22 Million Lines of Code (source: The Linux Foundation)

[Click on image for larger view.]

Nearing 22 Million Lines of Code (source: The Linux Foundation)

Following are some numbers that help understand the size, complexity and importance of the Linux kernel project, which hit version 4.7 last month:

- The kernel is made up of nearly 22 million lines of code.

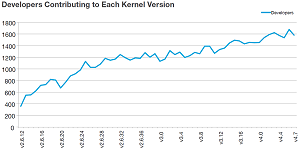

- 5,062 developers from more than 1,300 companies have contributed in the past 15 months (since the 3.18 release on Dec. 7, 2014).

- A new major kernel release occurs every nine to 10 weeks.

- During the period between the 3.19 and 4.7 releases, the kernel community was merging changes at an average rate of 7.8 patches per hour.

- Since the 2.6.11 release, the top 10 developers together have contributed 42,344 changes -- 7.5 percent of the total.

- H Hartley Sweeten led those developers, responsible for 5,960 changes. He's a systems integration engineer at Vision Engraving Systems in the Phoenix area, with the side title of "Linux Maintainer for the ARM/Cirrus EP93xx."

- Intel employed the most kernel developers in the 3.19 to 4.7 dev cycle (14,384), followed by Red Hat (8,987), Linaro (4,515), Samsung (4,338) and SUSE (3,619). Note that other company affiliations included none (8,571) and unknown (7,582).

- Since 3.19, the developers who added the most non-author signoff lines were led by Greg Kroah-Hartman, a fellow at The Linux Foundation (and co-author of the new report), with 13,992 .

- The total number of patches signed off by Linux creator Linus Torvalds (169, or 0.2 percent of the total) continues its long-term decline (he's delegating more work to subsystem maintainers).

- Red Hat leads in companies associated with employees doing signoffs (19,221 signoffs), followed by The Linux Foundation (14,180), Intel (12,640), Linaro (9,069) and Google (5,570).

[Click on image for larger view.]

Participation Continues To Grow (source: The Linux Foundation)

[Click on image for larger view.]

Participation Continues To Grow (source: The Linux Foundation)

One potentially worrisome statistic among all those numbers concerns the activity level of unpaid volunteers.

"Interestingly, the volume of contributions from unpaid developers has been in slow decline for many years," the report said. "It was 14.6 percent in the 2012 version of this paper, 13.6 percent in 2013, and 11.8 percent in 2014; over the period covered by this report, it has fallen to 7.7 percent. There are many possible reasons for this decline, but, arguably, the most plausible of those is quite simple: Kernel developers are in short supply, so anybody who demonstrates an ability to get code into the mainline tends not to have trouble finding job offers. Indeed, the bigger problem can be fending those offers off. As a result, volunteer developers tend not to stay that way for long."

Noting that the above finding was "potentially a cause for concern," the report dampened any alarmist interpretations.

"Might a shortage of volunteers lead to a shortage of kernel developers in the future?" the report said. "The situation is worth watching, but there are a number of reasons to not worry too much about it at this time. The first of those was mentioned above: successful volunteers tend not to stay volunteers for long; why do the work for free when somebody is willing to pay for it? But there is more to the story than that."

The report goes on to discuss in detail the "more to the story" aspects of the finding, and concludes: "The bottom line is that ... more than half of our new developers are paid to work on the kernel from their very first patch. In other words, companies working in this area have realized that one of the best ways to find new kernel development talent is to develop it in-house. So, for many developers, employment comes first, and it is no longer necessary to put in time as a volunteer developer. This fact, too, can explain the decrease in volunteers over time while simultaneously showing that the community as a whole remains healthy."

About the Author

David Ramel is an editor and writer at Converge 360.